Today, the logistics industry runs on paperwork and as members of the IT Billing team we are responsible for building the systems that handle the large volume of documents for our loads every year.

One challenge is that there are different rules that the system needs to apply based on what type of document is coming in to our system. In order to do that as a part of our current process, we have billing representatives ‘Index’ the document by looking at an image of the document and entering if it’s a bill of lading, carrier invoices, weight ticket or other type of document as well as the fields pertinent to that specific document type (i.e. a carrier invoice would have an invoice amount and an invoice date).

If we could automatically pull any information from the document or even just know what type of document we’re looking at ahead of time, we could make our document processing even more efficient. Every second saved over the course of 26 million documents a year would bring huge savings for our process.

Enter Data Science

Seeing the potential opportunities here, we struck up a conversation with our internal Data Science group during our annual Tech Showcase. After hearing more about and believing it was a solvable problem with some new technology, developer Chris Coughlin decided to see what he could do.

Optical Character Recognition (OCR)

First we tried a technique based on Optical Character Recognition (OCR) to identify document types. Our idea was to come up with a list of things we’d expect to frequently find in a Bill of Lading (BOL) (“Bill of Lading” being an obvious example), but that do not show up as frequently in other types of documents.

Since we didn’t need to actually extract information from the image, we could improve our chances of successfully identifying BOLs if we use “fuzzy” string matching instead of exact matches. If we go back to our “Bill of Lading” example, if the OCR finds “Bill of Lading” that’s a 100% match as you’d expect. On the other hand, if it instead claims to have found “Bit O’ Ladling” in the image, that’s still a 79% match to our expected string. We know that it’s unlikely for a transportation-related document to contain the words “Bit O’ Ladling”, so we accept this string as a positive match to “Bill of Lading”.

This approach tracked the difference between our target snippets and the text we found in the image so the smaller the difference between the two sets of text, the more similar the image is to a BOL and so the more likely the image is a BOL.

This approach was tested with a small batch of images that we had manually labeled as BOL or not BOL. It showed some initial promise, but there were two major concerns:

- Speed of classification - Each document must be scanned by the OCR process at multiple scales. This would have a major impact on the throughput (documents per second) of a production system.

- Sensitivity to orientation - If the document comes in upside down or rotated, the OCR process is unlikely to be able to extract text. We’d either need to accept that these documents wouldn’t be identified, or we’d have to guarantee that we’d always look at the correct orientation. The OCR approach looked like it might work in theory, but maybe not so well in practice.

Image Classification

Our next idea was to try image classification, in which a machine learning model is taught to recognize different classes of pictures. This used to be a very tedious task – gather millions of images, label each of them by hand, and then try to train a model.

Utilizing deep neural networks and transfer learning, we can dramatically shorten this process. We start with a model that someone else has already trained on a large dataset such as ImageNet. During its training, a model learns features of the images it examines to make its classifications. The features could be just about anything; lower layers of the deep learning network learn basic features like lines and corners and the upper layers learn more complex features like eyes and faces.

In transfer learning, we hope that the features a model has learned after being trained to classify one set of images are general enough that they’re useful in classifying a new set of images. If that’s the case, we don’t need to teach a model from scratch and we might only need to train on a few hundred or thousand labeled documents instead of millions.

To train our model, a training set of a few thousand images was assembled, augmented with their rotations through 90, 180, and 270 degrees. This increases the size of our training set (the more training data the better!) and helps set the model up to be able to handle document images that come in sideways or upside down.

After a few tweaks, we put a model into production behind a REST API to allow other systems to interact with it. In its first week in production the model examined more than 340,000 documents and was around 80% accurate in identifying BOLs and invoices.

It is difficult to know for certain what our model is zeroing in on to identify bills of lading. Early in testing, the model was trained on several hundred test documents to classify. This composite image is of the 50 most “BOL-like” of them:

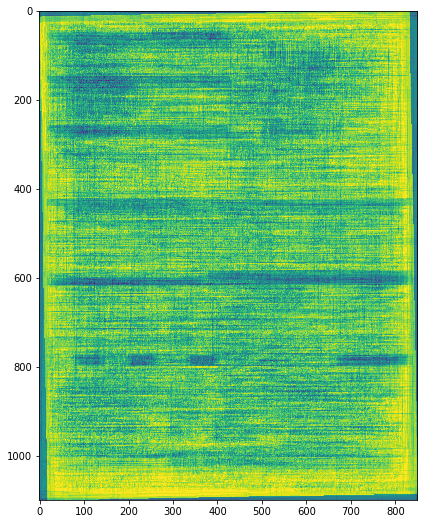

You can almost make out some horizontal features, but there doesn’t seem to be a whole lot there. Later, we tried the same with another model that performed better in our tests:

This model appears to be picking up on some of the layout features in your typical BOL, which often divide the page into several boxes to organize content.

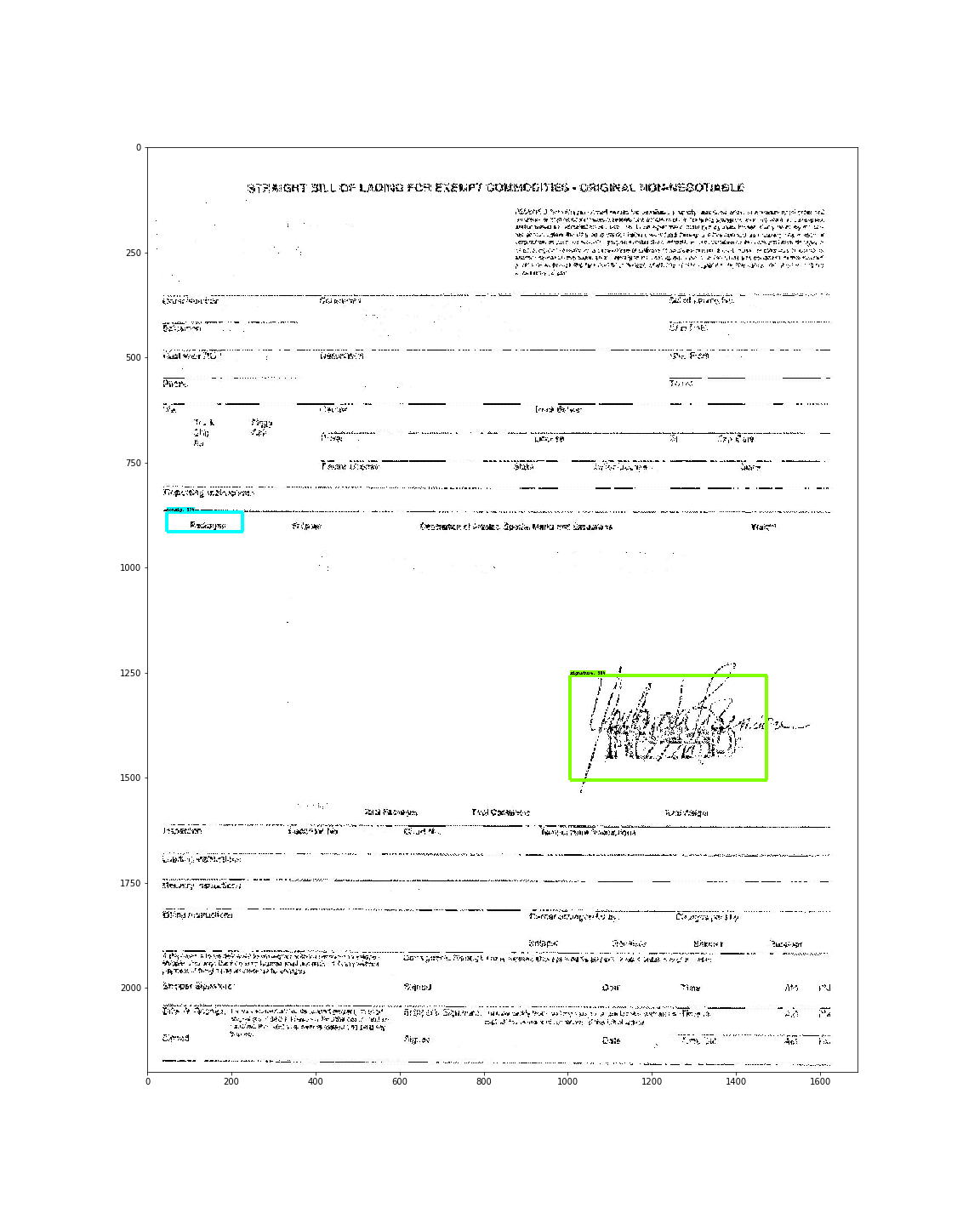

The next step is in determining whether a bill of lading has been signed by the consignee. This is a difficult challenge. A bill of lading might have signatures and handwriting, and could be print or cursive or both and all within the same document. A quick survey of previous research efforts seemed to suggest that it was possible to differentiate signatures from printed text and handwriting, so we thought: why not give it a shot and see what happens?

Our original plan was to curate a dataset of signed vs. unsigned BOL and train an image classifier on it, but even though the model looked promising in testing it hasn’t worked out as well as hoped in production.

Our current approach is to train a model to recognize signatures within a document. Rather than globally labeling a document as signed or unsigned, the program counts the number of signatures found within a document. If we find two or more, we’ll assume that the consignee has signed the BOL and we’ll report the document as signed. We can make this assumption because generally only two people will sign the document, the driver and the consignee. We’re still in the early stages of this approach, but the models we’ve built so far show some promise in being able to detect signatures, as seen below:

What’s Next?

The next steps will be to take these detection results and feed them into an auto-indexing engine. This engine will have different logic based on the type of document that is coming in to our system; correct automatic identification of the type of document will continue to be critical. Ideally, we’ll be able to capture enough data from the document automatically, so we can process documents faster and more efficiently, speeding up payments to our carriers and invoices to our customers, and reducing the workload on our people.

This auto-indexing process is a large piece of how C.H. Robinson is working to improve our billing process through cutting edge technology and automation. This process allows C.H. Robinson to remain on the forefront of customer service; our employees can spend less time on data entry and more time on what matters–the relationship with our customers and carriers.